Working with Text

Rethinking Reading Comprehension: Bringing Joy Back to Reading

When I was in elementary school, reading comprehension was one of my least favourite parts of the day. Typically, we’d be reading a class novel, and our comprehension work came in the form of a thick duotang filled with endless chapter questions. Most of them asked for random, surface-level facts, details that didn’t deepen our understanding or spark our thinking.

If you couldn’t answer a question, the teacher would remind you to “go back and find it in the book.” It wasn’t about thinking, it was about hunting for right answers. The process slowed down reading and, more importantly, drained the joy from it.

Fast forward to my first year of teaching, when I found myself unsure where to begin with reading and writing instruction. The teacher across the hall kindly handed me, ironically, stacks of comprehension booklets to go with our novel studies. So that’s what I did. It was all I knew.

Over time, though, as I grew in both confidence and experience, I began to search for something better. I wanted my students to love the books we were reading, to connect, question, and feel something, not just fill in blanks. Of course, comprehension still mattered, but I became convinced there had to be a more meaningful way to teach it.

That’s when I started exploring other approaches. I found open-ended graphic organizers that encouraged deeper thinking. I dove into the work of literacy experts like Faye Brownlie, Adrienne Gear, and Donalyn Miller, whose ideas reshaped my understanding of reading instruction. They reminded me that reading and writing are not worksheets, they are acts of creativity, curiosity, and connection.

When my teaching partner and I had the opportunity to design a school-wide literacy stations model, we wanted to make sure reading comprehension wasn’t reduced to another set of questions. We looked for ways to create a Working with Text station that was easy to differentiate, engaging, and tied directly to what we were already teaching in class.

We experimented; interactive notebooks (too much cutting and pasting!), digital tools, and countless templates. What worked best turned out to be simple, low-prep activities that built on what students were learning during whole-class lessons. For example, when we were teaching summarizing or finding the main idea and supporting details, students practiced those same skills during their literacy station time, but with texts at their own instructional level.

Our goal was to make comprehension practice feel like an extension of real reading, not an interruption to it. Once we had practiced an activity together, students could apply it independently, no matter what they were reading.

Because here’s the truth: reading comprehension doesn’t have to steal the joy of reading.

Students can jot down questions on sticky notes, highlight “show, don’t tell” moments, or find quotes that help them visualize the story, all while staying immersed in the text.

The purpose is the same: helping students think while they read. But the experience is entirely different. When comprehension becomes about curiosity instead of correctness, the joy of reading stays alive.

As teachers, we’re constantly balancing the “must-dos” of literacy instruction with our desire to help students fall in love with reading. The shift away from rote memorization work isn’t about abandoning rigour; it’s about reclaiming purpose. When students engage in authentic thinking; questioning, visualizing, connecting, and reflecting, they build the comprehension skills that truly matter.

In Making Time for It All, I talk about creating space for the kind of literacy learning that is comprehensive, high-quality, and joyful. That’s what rethinking comprehension is really about: making time for students to wonder, not just answer.

If you’re looking for ways to bring more meaning (and less paperwork) into your reading program, try replacing your next worksheet with a thinking prompt, a sticky note, or a short discussion that asks, “What made you think?” You might just find that comprehension and joy can grow side by side.

What are some of your favourite ways to support students reading comprehension?

Tiny Trinkets for Word Work

Little Trinkets for Big Thinking: Bringing Hands-On Learning Back to Literacy

There’s no shortage of manipulatives to support numeracy instruction; colourful cubes, counters, and fraction circles fill our math shelves. Yet, when it comes to literacy, the same level of tactile support is often missing. Decades ago, small alphabet trinkets were a classroom staple, tiny objects representing words beginning with each sound. Teachers who understood their power used them to build phonemic awareness and alphabetic knowledge long before the Science of Reading made those terms commonplace.

Over time, as pedagogical trends shifted, many of these small treasures were tucked away in cupboards or discarded altogether. But as Louisa Moats (2020) reminds us in her article, “Teaching Reading is Rocket Science,” it requires deep knowledge of how the brain learns to connect sounds to symbols, and intentional, explicit instruction that helps students map spoken language to print. We can’t leave that to chance. Today, with the growing momentum of the Science of Reading, teachers are once again seeking ways to make instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, and word recognition both meaningful and hands-on.

In my role supporting teachers and learning in classrooms, I often see educators spending hours searching online for alphabet images or cutting and pasting clip art just to create hands-on literacy centers. While these efforts show immense dedication, they also reveal how few ready-made resources exist to make foundational literacy instruction tangible.

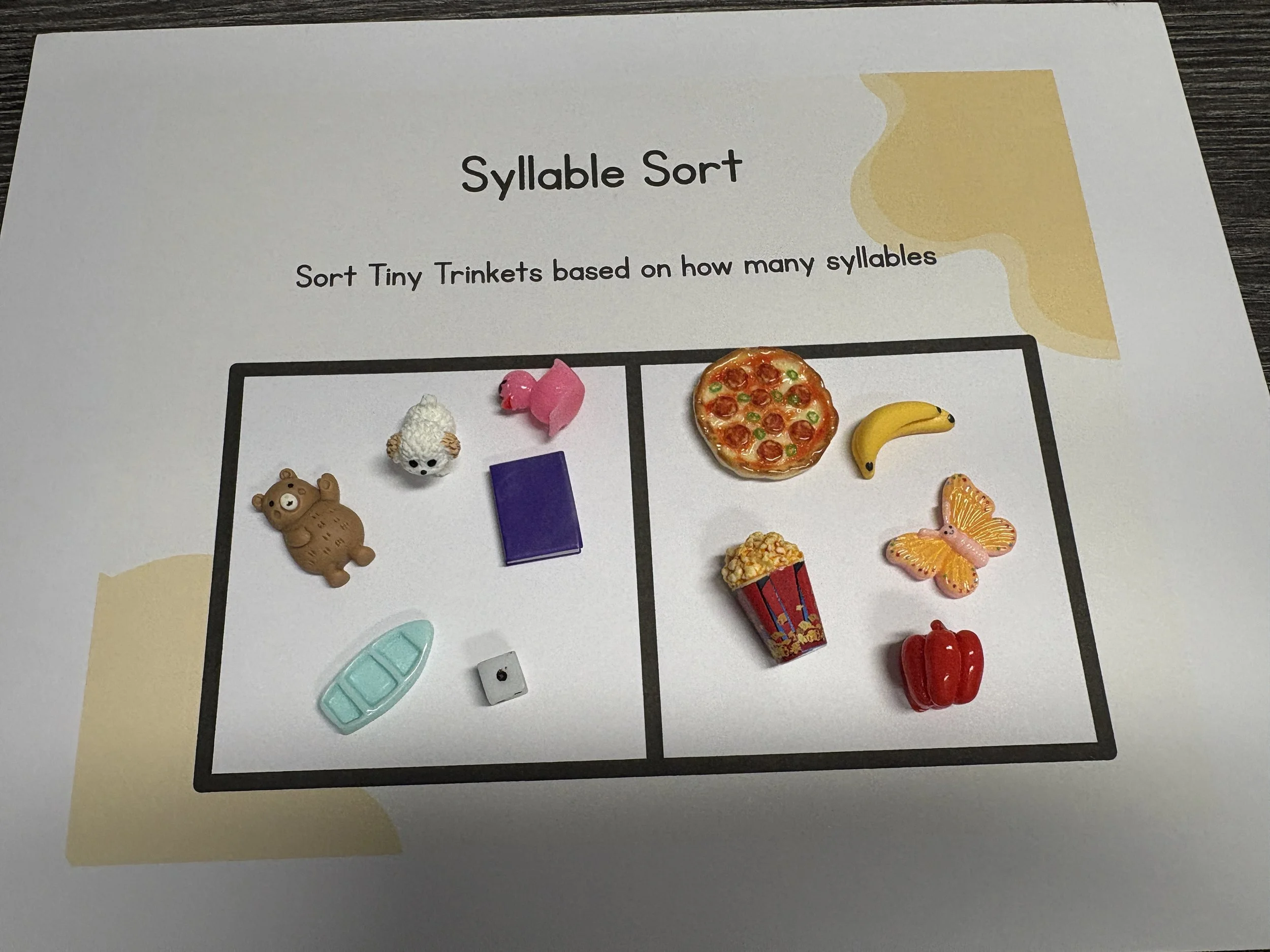

That’s where Little Trinkets for Big Thinking was born. Inspired by those classic alphabet buckets from the past, and grounded in current research, I’ve curated sets of small, meaningful objects designed to bring phonics and phonological awareness lessons to life. Each set is flexible, easy to differentiate, and engaging for young learners. Whether used to isolate beginning sounds, segment and blend phonemes, or build connections between sounds and letters, these trinkets make abstract concepts concrete.

When we give students opportunities to handle, name, and play with language through tactile materials, we make space for deeper understanding. We make time for what matters most, inspiring students to both love and learn to read and write.

Students use small items to practice skills in small groups or for independent practice.

Items can be used in so many different ways. As students develop their skills, they can use the items to practice a variety of different skills. These items can provide endless opportunities for independent practice and skill development.

Each box of items includes all 26 letters of the alphabet as well as TH, CH, SH, WH. Each letter box includes between 2-9 items. You can purchase the box of these items with a download of a 26 page activity book (for $198.95) under the Shop tab.

Love to Read

Silent reading after lunch time was a regular practice, both for me as a student and when I became a teacher. Sometimes as much as 40 minutes of class time was spent in “silent” reading. Back in the 90s when I went to high school, silent reading was prime note passing time. I guess we were reading, it just wasn’t our books. However, the premise of having students read during the day is an important one. Richard Allington tells us that everyday children are to read for choice. Yet, 30-40 minutes a week for independent reading time is as many as 200 minutes a week. For the many students who do not use this time for actual independent reading, this time can be used differently.

In my book, Making Time for it All, one of our literacy stations outlined is Love to Read. Here, during the station rotation students have time to read independently. One of my key mistakes when doing this early in my career was not teaching the students how to use this time effectively, nor what habits and practices make an effective reader. Additionally, when the station was over, I had students put their books away and quickly move on to the next station, without giving them an opportunity to talk about what they had read. Over the years, as I refined my literacy program, I built lessons, with explicit skill instruction, to help this station have more impact on student learning.

Love to Read Lessons

• What Do Good Readers Do: Explicit teaching on the building blocks of reading habits and practices: strategies for choosing books, concepts of print, and building stamina and engagement.

• Reading Comprehension: Instruction on making meaning while you read; tied to Working with Text.

• When I Don’t Know a Word: Explicit and systematic instruction on decoding strategies for students encountering a word they don’t understand in Love toRead; tied to Working with Words.

• Talking About Books: Lessons on the importance of reflection and synthesizing the information we learn while we read and sharing it with others.

Mentor Texts to help launch Love to Read

Mentor Texts to Help Launch Love to Read

To help support these lessons and introduce them to my students, I often use mentor texts. There are so many wonderful books available, and talking about them often helps students warm up to talking about themselves as learners. One of my favorites for the primary years is How to Read a Story by Kate Messner. This book is a playful “how-to” guide that models reading practices in a fun and accessible way. It’s easy to read, engaging, and sets the stage for students to create their own classroom “how-to-read” guidelines. In the older grades, it also works beautifully as a mentor text for writing their own “how-to” books.

Another favorite is Peter Reynolds’ The Word Collector. In this story, Jerome collects words from the world around him, discovering the beauty in language. In your classroom, students can be inspired to become word collectors themselves. A simple activity is to have students gather interesting words, explore their meanings, and share them with classmates. Creating a bulletin board or designated space for these words adds to the richness of a literacy-focused classroom, where reading and writing are part of the everyday environment.

Miss Brooks Loves Books (and I Don’t) by Barbara Bottner is another fun read aloud connected to the Love to Read station. This story is a wonderful launch point to discussing with your students finding the right book, and showing students that everyone can find a book they love. This book also helps introduce how there are many different types of texts out there and can help introduce the variety in your classroom or school library.

Sharing with your students the reason (the point) to reading, often opens up a fantastic classroom discussion. In the age of cell phones and reels reminding our students about the power of a good book is important. The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore by William Joyce, talks about the power of books and is a wonderful launch point for discussing with our students why we read.

Recipe for a great Love to Read as a Literacy Station

Books, Books, Books (and more!)

Fill your station with books and any other materials students might find interesting to read. I loved starting the morning by “selling” new books or texts to my students—sharing a quick pitch about why I thought they might enjoy them. If it has words on it and sparks curiosity, it belongs in Love to Read. Pamphlets, magazines, graphic novels, how-to instructions, menus, and lists can all have a home here.

A Comfy Spot to Read

Pillows, carpets, beanbag chairs, and cozy corners can all provide inviting spaces for reading. If you don’t have room for a dedicated corner, any spot will do! Give students freedom to find their own reading place, under desks, stretched out on the floor, or curled up on their stomachs.

Mini-Lessons to Build Skills

Teach students the “how” of independent reading so they can make the most of their time at Love to Read. Short lessons on building stamina, talking about books, and checking for understanding help set the tone and give students tools for success.

A Sharing Routine

Create opportunities for students to share what they’re reading; quick sharing, book commercials, or a class display of interesting words they have found. This builds community and helps students discover new books from one another.

Providing students with time to read for pleasure during the day is essential. It allows them to see the purpose behind learning to read, experience the joy of a good book, and discover new information. Celebrating reading, both individually and as a community, reinforces its importance and helps nurture a lifelong love of books.

Making Time for What Matters in the First Weeks of School

I got the call two days before the start of the school year; “we have a teaching position to offer you.” With only two days to prep a classroom before the beginning of the school year, I was a mess of nerves and excitement. After a quick stop at a few stores, I headed in to see my space for the first time. I spent hours decorating my classroom, it was “Pinterest worthy” before Pinterest was a thing. After two days my classroom was beautiful and ready to welcome students, but I hadn’t spent anytime thinking about what I was going to actually do with my students. I had heard I should be firm and not too friendly and make sure the students knew the rules of my classroom. Beyond that, I was winging it. After 25 years in this profession I have learned from trial and error, and watching great teachers, what the most important things to make time for in those first weeks of school.

Some great start of the year Mentor Texts to get to know your students.

1. Make Time for Relationships First

In a prior post, I talked about the importance of getting ot know your ingredients (your students). Getting to know your students is the most important thing you can do to set up your school year for success. Prioritize knowing students’ names, interests, and learning stories. Mentor texts can be a great way to do this, starting off having students talk about a story character is a low stakes way of introducing them to sharing more about themselves. We know that students learn best when they feel safe, known and valued. Getting to know your students, and allowing them to get to know you, creates a culture of trust that will set you up for a great school year.

Activities and Mentor Texts to Launch Them

Artifact box or bag— students bring small items that represent who they are and tell the story of their families culture and identity. Mentor Text - Matchbox Diary by Paul Fleischman

Same, Same but Different - have students connect with one another and create a venn diagram of the things they share in common (same) and the things that make them different. Mentor Text - Same, Same But Different

Book by Jenny Sue Kostecki-Shaw

What’s in a Name? - students will share the story of their name, and where it came from. If students don’t know they can interview a family member, or research what their names mean and where they originated. Mentor Text - Name Jar by Yangsook Choi, 2001, Alma and How She Got Her Name by Juana Martinez-Neal

2. Make Time for Building Routines and Classroom Culture

In my book Making Time for it All, I talk about the importance of setting routines early in the year. This can be an exhausting process, however, it sets your year up for success. When students are clear on the expectations and routines, they are better able to hit the target. When students are clear on the expectations and are partners in co-creating the expected norms, they thrive. Instead of creating a list of “rules” that are written in the negative, consider creating a list of agreements; I will do my best to learn. I will help others learn. You can point to these throughout the school year to remind students of expected behaviours.

Spending time building stamina in reading and writing, as well as outlining the expectations during your stations will allow for greater independence and success later in the year. Instead of cramming in all routines at once, layer them in, have students work on one or two routines and a time and build on them as they are successful. Don’t be afraid of stopping something in the middle of the lesson, or station, to reset the behaviours and remind them of the expectations (I often use humour when I do this to help keep it light). Relentless consistency is key.

Activities and Mentor Texts to Build Classroom Routines

Yet - students will learn the power of the word yet. The Magical Yet by Angela DiTerlizzi (Author), Lorena Alvarez Gómez (Illustrator)

Creating classroom norms - brainstorm with your students things that help their learning, vs hurt their learning. The Recess Queen by Alexis O’Neill

What do readers (and writers) do? - Helping students see examples of what the expected behaviour looks like, allows them to be clear on the expectations for themselves. Using a children’s story to talk about reading (and writing) behaviours is a fun way of setting the stage for the expectations in your classroom. Ralph Tells a Story by Abby Hanlon, How to Read a Book by Kwame Alexande

We can do hard things - Create a challenge for your students (build the tallest tower, pop a balloon, build a bridge using limited resources, untie a series of knots using only one hand each), after discuss the challenges and ask the students to reflect on the ways they persevered through the difficulties. Create an anchor chart where students can share the places they struggled, and kept trying. Jabari Jumps by Gaia Cornwall

3. Make Time for Joyful Reading and Writing

In British Columbia, one of our Big Ideas that runs through our K-9 curriculum is “Reading and Writing is a source of creativity and joy.” I believe this statement is foundational to our point as educators. We want our students to learn to read and write so that they can create and communicate, and enjoy it. Starting the year by finding the students interests can help you begin to find books and writing topics that the students would enjoy. I loved starting my school year (no matter the grade) reading Ralph tells a Story by Abby Hanlon, the idea that “Stories are Everywhere” is a great launch to exposing students to the love of reading and writing. In Donalyn Millers book the Book Whisperer she gives wonderful practical ways of creating a culture in your classroom that promotes a love of reading.

Having a space in your classroom where students can promote great books they have read, or share their own writing will help build and create a culture where reading and writing is celebrated. In one of the chapters of my book, I talk about book commercials, where students can share highlights of the books they are reading to tease their classmates and encourage them to want to read that book as well.

Mentor Texts

Reading Makes You Feel Good by Todd Parr, The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore by William Joyce, Rocket Learns to Read by Tad Hills

Ralph Tells a Story by Abby Hanlon, Ideas Are All Around by Philip C. Stead, A Squiggly Story by Andrew Larsen, The Best Story by Eileen Spinelli, Ish by Peter H. Reynolds

The start of the school year is both exciting and overwhelming. There can often be a lot of pressure to “hit the ground running” and begin ensuring that content and competencies are covered. Give yourself (and your students) permission to start off with the things that truly matter. Relationships, classroom culture and a love of learning. Not only is this a softer start, but it will set you up for a classroom year where students know they are known and loved and that they are clear on the expectations. Proactively beginning your school year this way, avoids much of the reactive behaviour management later on.

Know your Ingredients

Refrigerator Soup

My mom has a gift for cooking. She isn't fancy, but anyone who has ever gone to my parents’ house for dinner knows she’s a gifted cook. Her food (and her home) is full of love. My mom doesn't like waste and has a gift of using what she has and turning it into something extraordinary. I can't think of a better example of this talent than her “refrigerator soup.”

Many cooks have a recipe they love to follow, and with a few exceptions, they make it the same way every time. However, my mom is different. She looks at what she already has on hand, what vegetables are past their prime, and what ingredients complement each other, and then creates her recipe accordingly. If you sat at the kitchen table and watched my mom, I am sure you would wonder how on earth all the ingredients she pulls out of the fridge would work together. But every time, with love and patience, she makes it work. She would tell you that sometimes the results turn out better than others and rarely do the soups taste the same, but every time, my mom manages to make magic from the ingredients in our fridge.

My mom’s soup reminds me so much of teaching. Teaching isn't a recipe to follow; we don't get to pick our ingredients. Each year, our classroom fills with various ‘flavours’ ready to be incorporated into our classroom community. Just like with my mom’s soup, it’s essential to get to know the ingredients first; you’ve got to understand them before being incorporated effectively (and successfully) into the classroom. Each year, it will look different and will take some refining along the way. If we follow my mom's example, with lots of love and patience, we will look at the incredible gift of the students we receive in our classrooms and see what we can create together.

Getting to know our students is imperative to creating a classroom culture upon which our literacy structure can be built. Our students' interests, families, heritage, and culture are all essential aspects of who they are and meaningful ways for us to connect with them. Knowing more about who they are can help us connect them to texts and areas of interest that will support their reading, writing, and oral language skills.

Getting to Know you Activities

Artifact Bags

Read The Matchbox Diary by Paul Fleischman, highlight how the small items each told a story about the characters life. Show your students items that represent you and your identity (culture, family, interests). Have the students guess what these items tell about you. Ask students to bring a few small artifacts that represent them (their family, interests, culture, hobbies). Have the other students ask questions about the artifacts, or draw conclusions about what the artifacts may tell about the student. For younger students have them share what the items represent about their identity, for older students have them write about their identity and what the artifacts represent.

Same, Same But Different

Read the Story Same, Same but Different by Jenny Sue Kostecki-Shaw. Have the students compare and contrast the two main characters in a venn diagram. Then, pair the students up and have them do the same activity finding the similarities and differences between them and their classmates.

My Identity

Ask students to brainstorm what they think makes up an identity. Have them create a visual representation of the different things that make up their identity. Use any visual representation they want to represent themselves.

Pieces of Me

Design a 6-10-piece jigsaw puzzle with each piece showcasing a different part of your identity. For younger students send the activity home with parents to get them to help create the visuals for their child to help show who they are.

What are some activities you do at the beginning of the school year to get to know your students?

What’s your Point?

I grew up with educators as parents. My dad was a high school teacher and counsellor, and my mom went back to University later in life to become an elementary school teacher. I was incredibly privileged to have parents who created an environment at home where learning was encouraged, and we were fully supported. Early in my school career, my dad would sit beside me at the kitchen table and help with my homework. Whenever I wrote something, he always asked, “What’s your point?”. As I grew, I learned that I needed to have an answer to that question before sitting down with Dad for homework help. While writing my sixth-grade speech for the public speaking contest, I confidently sat down with what I knew was an excellent idea, only to hear my dad say, “Great ideas, what’s your point?”. This supportive question has become essential to my teaching philosophy: why am I teaching what I’m teaching, and why do the students need to know this?

In this digital age, we often find great lesson ideas on social media and decide to try them. While these ideas can be engaging, we sometimes realize that we are not clear on the learning objective or purpose behind the activity. Knowing your “point” is a critical aspect of teaching. Going in with a clear understanding of what you want and what you expect your students to learn brings clarity and direction to your lessons and your classroom. We can better hit the target when we know what we are aiming for.

Knowing your point, clearly, allows you to begin to find or create activities that are directly connected to your learning intention. Start with your point and then look for the ideas and activities to teach and practice that skill or concept.

Teacher Tip - Before planning a lesson or unit - What do you want students to know? How will you know they know it?

We can better hit the target when we know what we are aiming for.

Low Floor, High Ceiling Tasks

“I’m finished” and “I don’t understand”, two dreaded statements that often happen simultaneously after handing out an activity to your class. Fast finishers whip through the activity, often without challenge, and quickly shoot up their hand (or just yell out “I’M DONE.”) Emergent learners struggle to get started, often staring blankly at the page, raising their hand or simply sitting quietly at their desk, unable to start. These two statements became the bane of my teaching existence. I began creating tasks for my early finishers, and ran myself ragged trying to meet the needs of my emergent learners. No matter what I did I continued to feel like I was failing these groups of students (Shelley Moore calls these students the Outside Pins).

During one summer I was doing some reading on math instruction and I came across the statement “Low floor, High Ceiling tasks (LFHC)”. Peter Liljedahl spoke of creating rich math tasks that were open ended, meeting the needs of your most emergent (low floor) students and being open ended (high ceiling) to allow for your extending learners. I reflected on many of the tasks I had created for my students and realized there were some simple and creative ways I could remove the barriers to these activities to better meet the needs of all of my learners.

Tips to Creating LFHC Tasks

Know your point - I’ll likely write an entire post about the importance of this. But for now, know the target you want your students to hit. What skill or concept do you want them practicing? This simple question often helps you narrow the focus of your activities and weed out the activities that are really not teaching anything (my friend Faye calls this the “fluff”). Additionally, think about how you would like them to “Show that they Know” the point.

Know your Students - What can your most emergent learner do, and what skills do you need them to practice? What does your most extending learner need to feel challenged? If the point of your lesson is to work on identifying the phonemes in words; can you create an activity that as a low floor has students identifying specific initial sounds, and as a high ceiling, asks students to sort items based on either the initial, medial or final sounds. Create learning activities that considers these students ahead of time (proactively not reactively).

Explicitly teach and practice the skill - One of my critical mistakes was introducing an activity or worksheet at a station without teaching it, or practicing it first. As a whole class, explicitly teach the skill or concept and practice it together. In my early career we called this the “Gradual Release Model”. We taught it (I do), we practiced it together as a whole class (We do), and then students practiced it on their own (You do).

Remove the barriers - When designing your learning activity, think about what barriers will get in the way of the students learning. Is there a worksheet that has the students identify the initial sound of the picture shown? How could you create an activity that practices the same skill, but isn’t limited to the number (or sounds) of the pictures on the page. (Shameless plug - my Little Trinkets for Big Thinking kit and activities are a great LFHC way of practicing phonemic awareness)

There are some really simple ways to remove barriers from traditional activities. Once I know the learning goal, I begin searching for activities that will help students practice that skill. If I find a great activity, say in Canva, I ask myself how I might adapt it to become more of a Low-Floor, High-Ceiling (LFHC) task.

For example, if I want students to build their vocabulary knowledge, I won’t just give everyone the same list of words to find, define, and identify in a passage. Instead, I’ll teach students what to do when they come across an unfamiliar word while reading. As a practice activity, we’ll record words we don’t know (and want or need to learn), then work on defining and understanding their meanings.

In our literacy stations, students will use their “just right” texts to find words they’re curious about or don’t yet understand. The text becomes the differentiating factor, allowing students to learn vocabulary that is meaningful and instructionally relevant to them. They can then share their learning with others or add the new words to a shared word wall.

What are some great Low Floor, High Ceiling Tasks that you use in your Literacy stations or instruction. Share below.

See Below for some examples of ways to adapt activities to be more LFHC.

Making Time for It All

When I set out to write this book, I had no idea what an incredible gift it would be to reflect on my educational journey. I have been truly blessed by exceptional educators who generously shared their wisdom with me over the years. I am the product of the many people who inspired, guided, and supported me throughout my career.

As the child of two teacher parents, I grew up surrounded by a deep love of learning. My very first practicum experience was shaped by two remarkable mentors—seasoned educators who took me under their wings and showed me what lifelong learning truly looks like. They modeled the power of collaboration and innovation, and gave me the freedom to take risks.

Throughout my early career, I was fortunate to work alongside generous colleagues who shared their resources, their time, and their encouragement. I’ve had the privilege of working with principals who believed in me, leaders who gave me the permission to explore new ideas and supported my vision, even when it didn’t fit the mold.

And then there are the extraordinary women who spoke life into my career—mentors who challenged me, believed in me, and helped me see what was possible, even in moments when I couldn’t see it myself.

Writing this book has been a chance to revisit those moments and the many lessons I’ve learned along the way. It has reminded me of the joy in this journey, and deepened my desire to share what I’ve learned with others.

As I was writing this book, I chose to reach out to the people who made a difference in my career. Some of them I hadn’t spoken with in decades. In one instance, even though I spoke to her often, I decided to tell her all the ways she had impacted my life and my career. I told her I acknowledged her in my book and let her know how excited I was for her to read it. Two weeks later, she passed away suddenly. I am so grateful I took the time to say thank you and tell her about the impact she had on my life.

Who has inspired you? If you can, take a moment (or two) to think about the people who helped you become the educator (or person) you are today. Take it one step further, reach out to them and tell them they made a difference in your career and in your life. Don’t wait!